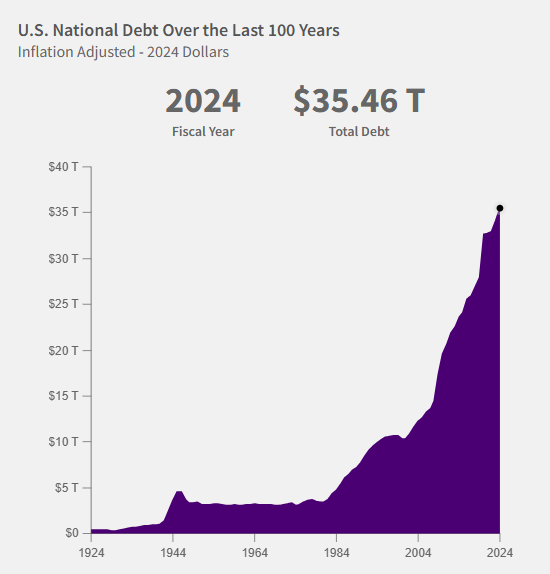

Long-Term Consequences of an Unchecked U.S. Federal Debt

Unchecked growth in federal debt would have profound economic effects and constrain policy. Mainstream analyses (CBO, IMF, Brookings, etc.) warn that rapid debt growth raises interest costs, crowds out investment and growth, and risks crises. In contrast, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) proponents note that a sovereign currency issuer can sustain high debt until inflation emerges, focusing instead on full employment and inflation controlcongress.govbrookings.edu. Below we detail the consequences and policy options, noting points of agreement and conflict between these views.

Economic Consequences of Rising Debt

Interest Payments and Budgetary Impacts

As debt rises, interest costs consume a larger budget share, crowding out other spending. For example, CBO projects federal debt at 156% of GDP by 2055cbo.gov, driving net interest from about 3.2% of GDP in 2025 to 5.4% by 2055cbo.gov. (By comparison, historical averages were around 2.1%.) Peter G. Peterson Foundation notes interest outlays reached $881B in 2024 and will nearly double to ~$1.8T by 2035pgpf.orgpgpf.org. Such soaring debt service “puts tremendous pressure on the federal budget, making it more difficult and costly to address pressing challenges and invest for the future”pgpf.org. In short, rising interest payments will eventually crowd out other priorities.

Moreover, CBO and analysts emphasize the compound effect: larger debt means higher rates raise debt-service costs even more, worsening deficits. CBO explicitly warns that “a larger debt is more vulnerable to an increase in interest rates,” since higher rates make servicing that debt much more expensivecbo.gov. In practice this means deficits would grow even if tax and spending policy stayed unchanged – a dangerous feedback loop.

(MMT perspective: MMT proponents note that because the U.S. borrows in its own currency, the government can always “self-finance” interest by issuing more moneybrookings.edu. In other words, there is no technical solvency limit like a household’s. Interest would then be inflationary rather than a cash crunch, so deficits per se are not an immediate fiscal constraintcongress.govbrookings.edu. In MMT view, taxes are used to manage inflation, not to “pay down” debt. *)

Effects on Investment, Growth, and Wages

High debt crowds out private investment, weakening growth and wage prospects. Every additional dollar borrowed by the Treasury competes for savings, leaving less capital for businesses. CBO estimates that each $1 of deficit cuts private investment by roughly $0.43cbo.gov, which over time shrinks the capital stock and slows output. As CBO explains, “increased federal borrowing… drives up interest rates, which raises borrowing costs in both the public and private sectors. As a result, investment in capital used to produce goods and services decreases,” leaving workers with “fewer resources to do their jobs”cbo.gov. In plain terms, smaller capital-per-worker means lower productivity and wages.

Quantitatively, rising debt notably dims income growth. Analysis by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) of CBO’s projections finds that under the baseline debt path, income per person grows about 12% more slowly over 30 years than it would if debt were stabilized. If debt rose even faster (nearly 300% of GDP by 2054), CRFB shows growth could slow by one-thirdcrfb.orgcrfb.org. Brookings likewise warns that, even absent a crisis, “future generations will be worse off” when higher debt has pushed up rates and crowded out investment, leading to “slower productivity growth” and lower living standardsbrookings.edu.

PGPF summarizes: “issuing such large amounts of federal debt…could ‘crowd out’ investments by the private sector, making the economy less productive and stunting wage growth”pgpf.org. Indeed, empirical evidence supports the standard crowding-out effect: a CBO study found each 1% of GDP increase in the debt ratio boosts real 10-year Treasury yields by ~0.02%, implying several tenths of a point higher rates due to projected debt growthpgpf.org. That rise in rates both deters private investment and implies higher borrowing costs for businesses and consumers.

(MMT perspective: By contrast, MMT-inspired analysis would argue that public debt and deficits per se can boost “aggregate demand” and thus growth, especially when the economy has unused capacity. For MMT, deficits that finance valuable investments (infrastructure, education, etc.) can raise productivity and support wages. They generally dismiss the crowding-out view, since in a liquidity-trap or low-rate environment public borrowing need not compete with private firms. In that view, as long as inflation is contained, increased public investment can raise GDP without hurting private sector investment. Critics counter that in normal times (as CBO assumes), expanded deficits do bid up rates and compete for funds, confirming the crowding-out mechanism. *)

Inflation and Fiscal Crisis Risks

A large debt raises the risk of inflationary pressures and fiscal or financial crises. If markets ever doubted the U.S. government’s creditworthiness, borrowing costs could spike. Brookings defines a fiscal crisis as a sudden shift that “triggers a sharp and persistent spike in interest rates, probably accompanied by a steep fall in the value of the U.S. dollar” and financial turmoilbrookings.edu. CBO likewise warns that perpetual debt growth would heighten the likelihood of such a crisis, one that could force abrupt austerity with “substantial pain” or even a default if unaddressedcbo.govcbo.gov.

Inflation is another key risk of large deficits. In conventional models, excessive government spending (or money creation to finance debt) can overheat demand. While recent deficits have occurred amid low inflation, mainstream analysts caution that if deficits outpace supply capacity, prices could accelerate. For example, IMF analysis notes that persistently higher interest rates from debt servicing “pose risks to financial stability” and can feed inflation expectationsimf.org. The Yale Budget Lab also finds elevated debt raises inflation pressure via demand channels (though not cited here). In CBO’s view, higher inflation expectations could “erode confidence in the U.S. dollar as the dominant international reserve currency”cbo.gov. (In practice, moderate inflation modestly reduces real debt burdens, but runaway inflation imposes its own economic costs.)

(MMT perspective: MMT explicitly holds that inflation – not debt level – is the true constraint. MMT proponents agree that if deficits push the economy beyond capacity, inflation will accelerate. As Senate testimony quotes Stephanie Kelton, “MMT’s arguments largely boil down to…how much room there is to borrow without accelerating inflation”congress.gov. Thus, MMT would say debt is fine as long as it doesn’t cause inflation; taxes are the tool to curb excess demand. Modern Monetary theorists see no inherent default risk in a sovereign currency issuer – a point echoed by Krugman and Buffett – but mainstream economists reject that notion, emphasizing that high debt still “reduce[s] future national saving… and drag[s] down future national income”brookings.edu. In short, both sides recognize inflation as a concern, but MMT sees it as the binding limit while others worry about loss of market confidence even before runaway inflation. *)

Impact on the U.S. Dollar’s Reserve Status

The U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency currently gives America an “exorbitant privilege” – able to borrow cheaply and run deficits with less immediate falloutcfr.orgcfr.org. About 60% of global reserves are in dollars, and dollar-denominated assets account for two-thirds of international securitiescfr.orgbrookings.edu. This demand helps keep Treasury yields lower, since foreign central banks and investors buy U.S. debt as a safe asset.

However, an unbounded rise in debt could gradually erode that confidence. In the extreme, if investors feared inflation or large losses on Treasuries, they might diversify away from dollars and Treasuries. CBO explicitly lists “expectations of higher inflation” as a factor that could sap confidence in the dollar’s hegemonycbo.gov. Brookings notes the dollar’s share of reserves has fallen (from ~70% in 2000 to ~59% today) as some countries hold other stable currenciesbrookings.edu. Still, most experts believe the dollar will remain dominant for now: vast capital markets, deep liquidity, and a stable U.S. economy make it hard to replacecfr.orgbrookings.edu. In practice, only if debt growth triggered a loss of confidence would the dollar’s status materially weaken.

(Broad view: Many economists argue that worries of “de-dollarization” are overblown in the short run. The IMF finds that while the dollar’s share of reserves has declined slowly, no single alternative currency has decisively challenged itimf.orgimf.org. As one expert notes, “It’s more helpful to think of U.S. treasuries as the world’s leading reserve asset… It’s hard to compete with the dollar if you don’t have a market analogous to the Treasury market”cfr.org. In summary, while growing debt could in theory make foreign investors nervous, the U.S. retains unique financial depth. If debt undermines fiscal stability, however, the dollar’s appeal might gradually wane, forcing higher borrowing costs and inflation (a scenario mainstream analyses include as part of fiscal-crisis risk). *)

Policy Options to Manage or Reduce the Debt

No single policy can erase decades of deficits. Analysts agree a combination of reforms – on taxes, spending, growth, and institutions – would be needed. Below are key approaches often discussed by policymakers and economists:

- Revenue-Side Solutions: Raise or reform taxes. CBO has catalogued dozens of options. Common proposals include broadening the tax base (eliminating or limiting deductions and loopholes), raising top marginal rates on individuals or corporations, and introducing new levies like a value-added tax (VAT) or carbon taxpgpf.orgpgpf.org. For example, eliminating all itemized deductions could raise ~$3.4 trillion over 10 yearspgpf.org, and a 5% VAT might raise ~$2–3 trillionpgpf.org. Other ideas include a surtax on high incomes or expanding wealth and estate taxespgpf.org. Washington’s 2017 tax cuts made revenues more vulnerable, so many analysts argue targeting revenue growth is essential.(MMT perspective: MMT scholars generally view tax policy differently. They do not advocate taxes solely to pay down debt, but instead use taxes to manage inflation or redistribute wealth. Thus an MMT advocate would support, say, higher taxes on the wealthy for equity or inflation reasons, but would not claim that these taxes are needed to “afford” the debt. In practice, MMT proponents have supported some tax hikes (e.g. “Millionaire’s Tax”) as a way to curb inflation without slowing the economy, which coincides with mainstream ideas on progressive taxation.)*

- Spending-Side Solutions: Cut or restrain federal outlays. Most debt-reduction plans focus on entitlements and discretionary spending. CBO and fiscal commissions have outlined many options:

- Entitlements (mandatory spending): Since Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid together drive long-term debt, even modest reforms can yield large savings. For instance, placing caps on federal Medicaid funding (either per-enrollee or per-state) could save ~$0.5–0.9 trillion over 10 yearspgpf.org. Capping Social Security benefits at a fixed level (e.g. a uniform benefit tied to poverty) could trim $0.3–0.6 trillionpgpf.org. Other ideas include gradually raising the retirement age, means-testing benefits, or slowing the growth of Medicare payments. The failed 2010 Simpson-Bowles plan, for example, would have slowed health-care spending growth and raised the Social Security agecfr.org.

- Defense and Other Discretionaries: Defense is the largest discretionary category (~3% of GDP). Proposed cuts range from trimming forces to reforming procurement. CBO estimates that reducing the Department of Defense budget (e.g. smaller forces, fewer combat units) could save roughly $959 billion over 10 yearspgpf.org. (However, most experts note defense is already near a historical low share of GDP, so deep cuts may be difficult politicallybrookings.edu.) Other discretionary savings include smaller reductions in domestic agencies, though these are generally much smaller dollar-wise. In practice, any broad deficit plan would combine entitlement reforms with some discretionary restraint.

(MMT perspective: MMT tends to oppose austerity cuts, especially in downturns, arguing that public spending is needed to sustain full employment. MMT supporters would warn that cutting investment (infrastructure, education, health) could shrink GDP and raise debt/GDP in the long run. They also emphasize that social programs can boost growth by raising human capital. Thus an MMT-centric strategy would likely favor maintaining or expanding high-multiplier spending, with any fiscal restraint coming via higher taxes when inflation, rather than debt, is the issue.)*

- Growth-Based Strategies: Any strategy stresses the role of economic growth in stabilizing the debt ratio. Faster GDP growth raises tax revenues and shrinks debt/GDP. History shows that strong growth has helped correct imbalances (e.g. post–WWII). CBO notes that the post-war debt decline was largely due to booming growth and modest surpluses, not just cutsbrookings.edu. In today’s context, growth opportunities include investing in infrastructure, education, research & development, and policies to boost labor force participation (e.g. immigration, child care, retraining). Regulatory reforms and trade liberalization can also lift productivity.However, experts caution that growth alone is unlikely to “solve” the debt issue without policy changes. Brookings points out that demographic headwinds (aging population) and already-low interest rates mean we can’t count on a post-war miracle of growthbrookings.edu. Still, pro-growth reforms are part of the mix: the CBO shows that under a higher-productivity scenario, debt in 2054 would be far lower (124% vs 166% GDP)cbo.gov. In practice, growth strategies complement fiscal reforms rather than replace them.(MMT perspective: MMT strongly supports using fiscal policy to achieve full employment and higher growth. A job guarantee (public employment at a social wage) is one MMT proposal to stabilize employment. While traditional policy often relies on monetary policy for growth, MMT advocates use budget deficits to counteract downturns. This aligns with mainstream calls to invest in growth, but MMT would not trade growth for lower debt – deficits would fund whatever full-employment policies are needed, constrained by inflation.)*

- Structural Reforms: These are changes to fiscal rules or institutions. Two examples:

- Debt Ceiling and Rules: Many analysts argue the U.S. debt ceiling is anachronistic and self-defeating. As CFR expert Brad Setser argues, the U.S. should abolish the debt ceiling entirelycfr.org so as to avoid manufactured crises. Others (e.g. Furman and Summers) say Washington should “end its debt obsession,” implying rules that rigidly target debt ratios may be counterproductivecfr.org. Reform ideas include automatically raising the ceiling to GDP or excluding emergencies.

- Automatic Stabilizers and Pay-As-You-Go: Strengthening automatic stabilizers (like unemployment insurance, food stamps, the Earned Income Tax Credit) can help deficits only rise in recessions and fall in expansions, smoothing the debt path. Similarly, implementing PAYGO rules (requiring new spending/tax cuts to be offset) can force discipline. These are often discussed on the Hill, though economists note they are only partly effective unless strictly enforced.

(MMT perspective: MMT proposals often overlap with structural ideas. MMTers would strengthen automatic stabilizers and endorse flexible fiscal rules tied to inflation or employment, rather than arbitrary debt targets. They generally oppose hard caps (like PAYGO) if it means cutting beneficial programs. Instead, an MMT-informed reform might index some spending or taxes to economic indicators. On the debt ceiling, MMT critics also call it destructive – seeing it as a political fiction that threatens needless default.)*

- Trade-offs and Timing: Almost all analysts emphasize timing. CBO’s modeling shows the longer reforms are delayed, the larger the needed changes. Early, modest changes can flatten debt, while waiting forces steeper cuts or tax hikescbo.govbrookings.edu. For instance, CGD analysts estimate that stabilizing the debt/GDP ratio at 99% by 2054 would require enduring about 2.7% of GDP in permanent tax hikes and/or spending cuts (roughly $750B/year) if started promptlybrookings.edu – and much more if postponed. This classic result (“debt doesn’t matter until it does”) is summarized by Maya MacGuineas: “By taking advantage of our privileged position… we may well lose it.”cfr.org.

Contrasting Perspectives: Traditional Economics vs. MMT

Consensus (Mainstream) View: Most economists agree that very high debt/GDP has downsides. Institutions like CBO, IMF, Fed economists and nonpartisan analysts focus on solvency risks (rising interest outlays, crowding out, crisis probability). They warn that even if default is unlikely, high debt constrains policy. For example, CBO and Brookings emphasize crowding-out and growth dragcbo.govbrookings.edu. They treat debt as a burden on future taxpayers and investors. Inflationary risk is also noted, though usually as a second-order concern compared to debt-service and crisis risks.

MMT/Heterodox View: MMT proponents start from the premise that the U.S. cannot involuntarily default on its dollar debts. Debt is simply the mirror of the government’s deficit spending (private sector savings plus Fed balances). Famous advocates (like Stephanie Kelton) argue that government deficits “pay their own way” by injecting money into the economybrookings.edu. From this standpoint, the only real limit is inflation. Taxes primarily manage inflation (by reducing spending power) and inequities, not to “fund” spending. MMTers would emphasize that until the economy is at full capacity, government spending can raise output without sparking inflation.

Points of Agreement: Both schools recognize that runaway inflation would be harmful. MMT explicitly agrees that inflation is the binding constraintcongress.gov. Hence both sides might endorse raising taxes or cutting spending if inflation were rising too fast. In practice, neither side says “anything goes forever.” Both would likely support sustainable deficits or surpluses at full employment.

Points of Conflict: The main disagreement is how fast debt matters. Traditional economists argue that even at moderate inflation, excessively high debt erodes savings, crowds out investment, and creates crisis riskcbo.govcbo.gov. In contrast, MMT proponents contend these are overstated: sovereign debt can always roll over. They would typically oppose preemptive austerity (tax hikes or spending cuts) unless inflation demanded it. As former Fed Chair Bernanke put it, the “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar means the U.S. can incur heavy debt more easily than mostcfr.org.

In summary, mainstream policy emphasizes balancing debt concerns against current needs (often urging gradual fiscal consolidation), while MMT-influenced voices emphasize the benefits of fiscal flexibility and focus on inflation. A compromise view might accept both: use fiscal stimulus to support growth when slack exists, but be ready to rein in deficits (via taxes or cuts) if inflation picks upcongress.govcongress.gov. As one broad assessment notes, even MMT “admits that deficits and debt matter” ultimately – the debate is over how and when they mattercongress.govbrookings.edu.

Sources

Key sources include the Congressional Budget Office’s recent Long-Term Budget Outlookcbo.govcbo.gov, analyses from the Brookings Institution and nonpartisan budget groupsbrookings.educrfb.org, and think-tank reports (PGPF, CRFB) on debt dynamicspgpf.orgpgpf.org. IMF and Fed studies also highlight fiscal risksimf.org. The Modern Monetary Theory perspective is represented by statements from its advocates (e.g. Kelton) and critiques in resolutionscongress.gov and op-edsbrookings.edu. These together delineate the trade-offs as Congress debates the U.S. fiscal path.